- Signal recently launched a beta integration of MobileCoin (MOB) for payments. Its price has jumped from $7 to over $55 in the past month.

- Signal founder Moxie Marlinspike, whom MobileCoin previously described as a technical adviser, may have been more deeply involved in the cryptocurrency project.

- An earlier, nearly identical white paper found online, which MobileCoin CEO Joshua Goldbard called „erroneous,“ lists Marlinspike as the project’s original CTO.

The founder and CEO of encrypted messaging app Signal, Moxie Marlinspike may have been the former CTO of MobileCoin, a cryptocurrency that Signal recently integrated for in-app payments, early versions of MobileCoin technical documents suggest.

MobileCoin CEO Joshua Goldbard told CoinDesk this 2017 white paper is “not something [he] or anyone at MobileCoin wrote,” though it is very nearly a verbatim precursor to MobileCoin’s current white paper. Additionally, snapshots of MobileCoin’s homepage from Dec. 18, 2017, until April 2018, list Marlinspike as one of three members of “The Team,” though his title is not given there. He is not listed as an adviser until May 2018.

The team for the self-described privacy coin has always acknowledged Marlinspike as an adviser to the project, but neither the team nor Marlinspike has ever disclosed direct involvement through an in-house role, much less one so involved as Chief Technical Officer.

If Marlinspike actually was involved as a CTO in MobileCoin’s early days, the recent Signal integration raises questions of MobileCoin’s motivation for associating itself with the renowned cryptographer, along with his own motive for aligning with the project, given the MOB team has historically downplayed this involvement.

“Signal sold out their user base by creating and marketing a cryptocurrency based solely on their ability to sell the future tokens to a captive audience,” said Bitcoin Core developer Matt Corallo, who also used to contribute to Signal’s open-source software.

Goldbard shared another document dated Nov. 13, 2017, same as the other white paper, which does not list a team for the project. He claimed that this white paper was the authentic one and the other was not.

“Moxie was never CTO. A white paper we never wrote was erroneously linked to in our new book, ‘The Mechanics of MobileCoin.’ That erroneous white paper listed Moxie as CTO and, again, we never wrote that paper and Moxie was never CTO,” Goldbard told CoinDesk.

This book is actually the most recent “comprehensive, conceptual (and technical) exploration of the cryptocurrency MobileCoin” posted on the MobileCoin Foundation GitHub, which Goldbard describes as project’s “source of truth” and serves as the most up-to-date technical documentation for the project.

This ”real” version of the paper is nearly identical to the “erroneous” white paper except there is no mention of team members or MobileCoin’s pre-sale details. (Both white papers and current MobileCoin technical documents are embedded at the end of this article for reference.)

Goldbard said the “erroneous” white paper was accidentally added as a footnote to this latest collection of technical documents compiled by Koe, a pseudonymous cryptographer who recently joined MobileCoin’s team. That footnote also lists Marlinspike as a co-author of the paper along with Goldbard.

“He just googled it, like everyone on the internet seems to be doing today, and put [it in] as a footnote. It was an oversight. I did not notice it in my review of the book prior to publishing,” Goldbard told CoinDesk.

A metadata analysis of the papers run by CoinDesk shows that the “erroneous” paper was generated on Dec. 9, 2017, while the “real” paper was generated two days later.

Marlinspike declined to comment on the record about his professional relationship with MobileCoin.

A tale of two papers

In a December 2017 Wired article titled “The Creator of Signal Has a Plan to Fix Cryptocurrency,” Marlinspike went on the record as a “technical adviser,” a title CoinDesk has also used to describe his relationship with MobileCoin in the past.

“There are lots of potential applications for MobileCoin, but Goldbard and Marlinspike envision it first as an integration in chat apps like Signal or WhatsApp,” the article reads.

It also states that “Marlinspike first experimented with [Software Guard Extensions (SGX)] for Signal.” These special (and expensive) Intel SGX chips create a “secure enclave” within a device to protect software, and MobileCoin validators require them to function (validators, as in other permissioned databases, are chosen by the foundation behind MobileCoin).

Source: https://www.coindesk.com/signal-founder-may-have-been-more-than-tech-adviser-mobilecoin

Marlinspike argues, Signal didn’t enable those criminals, but instead simply made their tools available to more casual, non-criminal users.

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/signal-mobilecoin-payments-messaging-cryptocurrency/

Signal Adds a Payments Feature—With a Privacy-Focused CryptocurrencyThe encrypted messaging app is integrating support for MobileCoin in a bid to keep up with the features offered by its more mainstream rivals.

MobileCoin will bring payments to Signal, but also added complexity and potential regulation. Illustration: Elena Lacey

MobileCoin will bring payments to Signal, but also added complexity and potential regulation. Illustration: Elena Lacey

To try to tame that volatility problem, Marlinspike and Goldbard say they imagine adding a feature in the future that will automatically exchange users‘ payments in dollars or another more stable currency for MobileCoin only when they make a payment, and then exchange it back on the recipient’s side—though it’s not yet clear if those trades could be made without leaving a trail that might identify the user. „There’s a world where maybe when you receive money, it can optionally just automatically settle into a pegged thing,“ Marlinspike says. „And then when you send money it converts back out.“The mechanics of how MobileCoin works to ensure its transactions‘ privacy and anonymity are—even for the world of cryptocurrency—practically a Rube Goldberg machine in their complexity. Like Monero, MobileCoin uses a protocol called CryptoNote and a technique it integrates known as Ring Confidential Transactions to mix up users‘ transactions, which makes tracing them vastly far more difficult and also hides the amount of transactions. But like Zcash, it also uses a technique called zero-knowledge proofs—specifically a form of those mathematical proofs known as Bulletproofs—that can guarantee a transaction has occurred without revealing its value.On top of all those techniques, MobileCoin takes advantage of the SGX feature of Intel processors, which is designed to allow a server to run code that even the server’s operator can’t alter.

MobileCoin uses that feature to ensure that servers in its network are deleting all lingering information about the transactions they carry out after the fact and leave only a kind of cryptographic receipt that proves the transaction occurred. Goldbard compares the entire process of a MobileCoin transaction to depositing a check at a bank, but one in which the check’s amount is obscured and it’s mixed up in a bag with nine other checks before it’s handed to a robotic bank teller. After handing back a deposit slip that proves the check was received, the robot shreds all 10 checks. „As long as SGX is working as promised, you can prove every robot cashier is working the same way and shredding every check,“ Goldbard says. And even if Intel’s SGX fails—security researchers have found numerous vulnerabilities in the feature over the last several years—Goldbard says that MobileCoin’s other privacy features still reduce any ability to identify users‘ transactions to low-probability guesses.If MobileCoin’s privacy promises hold true, Marlinspike says he hopes the cryptocurrency can help Signal reverse a troubling trend toward financial surveillance. If successful, Signal’s use of MobileCoin will also face the same hurdles and critiques that surround all privacy-preserving cryptocurrencies. Any technology that offers a way to anonymously spend money raises the specter of black market uses—from drug sales to money laundering to the evasion of international sanctions—along with the accompanying crush of financial regulations. And that means integrating MobileCoin could expose Signal to new regulatory risks that don’t apply to mere encrypted communications.

„I think it’s phenomenal from a civil liberties perspective,“ says Marta Belcher, a privacy-focused cryptocurrency lawyer who serves at special counsel at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. But Belcher points to a coming wave of regulation to control exactly the sort of anonymous cryptocurrency transactions Signal hopes to enable, including a new „enforcement framework“ the Justice Department published last fall and new regulations from FinCEN that could force more players in the cryptocurrency industry to collect identification details of users. „Anyone who’s dealing with cryptocurrency transactions, especially private cryptocurrency transactions, should be really concerned about all of these proposals and the government pushing financial surveillance to cryptocurrency,“ Belcher says.Matt Green, a cryptographer at Johns Hopkins University, puts it in starker terms.

„I’m terrified for Signal,“ says Green, who helped develop an early version of Zcash and now sits on the Zcash Foundation board as an unpaid member. „Signal as an encrypted messaging product is really valuable. Speaking solely as a person who is really into encrypted messaging, it terrifies me that they’re going to take this really clean story of an encrypted messenger and mix it up with the nightmare of laws and regulations and vulnerability that is cryptocurrency.“But Marlinspike and Goldbard counter that Signal’s new features won’t give it any control of MobileCoin or turn it into a MobileCoin exchange, which might lead to more regulatory scrutiny. Instead, it will merely add support for spending and receiving it. „The regulatory landscape is complicated, but there are ways to do privacy-protecting payments safely,“ says Goldbard. „To be frank, there’s a moral imperative to do so, because Signal has to offer payments in order to remain competitive with the world’s top messaging apps.“As for the possibility of enabling dangerous criminals and money launderers, Marlinspike offers an answer that mirrors one he’s long given for encrypted communications. Just as criminals used encryption for decades before Signal, they’ve used anonymous cryptocurrencies for years before Signal added MobileCoin payments as a feature.

For those criminals, the threat of law enforcement made using even clunky, tough-to-use tools necessary. By making those secure communications and payments easier, Marlinspike argues, Signal didn’t enable those criminals, but instead simply made their tools available to more casual, non-criminal users.“With Signal, we didn’t invent cryptography. We’re just making it accessible to people who didn’t want to cut and paste a lot of gobbledegook every time they sent a message,“ Marlinspike says. „I see a lot of parallels with this. We’re not inventing private payments…Privacy preserving cryptocurrencies have existed for years and will continue to exist. What we’re doing is just, again, a part of trying to make that accessible to ordinary people.“

The Messenger Alternatives

Some use the internet, some function without servers, some are paid and others are free, but all these apps claim to have one thing in common—respect for user privacy

Image: Jaap Arriens/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Image: Jaap Arriens/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Ever since WhatsApp announced an update in its privacy policy, thousands of people rushed to download messenger alternatives such as Signal and Telegram. While these two have been in the news for their security features that are tighter than the messaging giant’s, there are other applications that have been around, used for both facilitating consumer-to-consumer messaging and within enterprises for their internal communication.While some of these alternative apps need the internet, others don’t. Some function without servers with peer-to-peer technology, and are on a subscription model, while others are free to use. But they all claim to have one thing in common–respect for users’ privacy.

Although security and privacy-related technologies are constantly evolving making it difficult to lay down a clear benchmark for which app is completely secure, there are a few things users should be aware of to ensure their privacy is not compromised, say technology and privacy experts.First, says Divij Joshi, technology policy fellow at Mozilla Foundation, a global non-profit, “It’s definitely important to have a communications protocol based on end-to-end encryption.”End-to-end encryption refers to a system of communication wherein only the sender and receiver can read the messages and see the content shared.However, Joseph Aloysius, a Singapore-based student researcher in surveillance studies, says, “Even with encryption it is important that it is device-based end-to-end encryption, and not cloud-based. In addition, the encryption setting should be a default setting, not optional as seen in Telegram.”Another point to keep in mind is to ensure that technologies collect as little metadata–information not related to the message content but things like quantum or location of messages–as possible, adds Joshi.Second, they should be open source and left open for public auditing. “Ideally, it’s best if companies leave the server code open as Signal has done,” says Aloysius.Both Joshi and Aloysius are of the view that it is also necessary to ensure that the corporate practices of the application are clear and fair. “For instance, terms of use, the privacy policy, so they can’t alter the technology or data collection practices arbitrarily,” says Joshi.Although there has been an uproar about the latest changes to the privacy policy, WhatsApp continues to remain popular primarily due to its ease of use and convenience, say experts. “For some, it may also be a cost concern. There may also be a false sense of security since nothing apparent has gone wrong and there have been no consequences to date for them using the app for business purposes,” explains Heidi Shey, principal analyst, security and risk, Forrester.However, if you are a user who is concerned about privacy, here is a lowdown on alternatives to WhatsApp and the features they offer.Wickr

The San Francisco-based app, founded in 2012, is used by some of the biggest players in the federal space including the U.S. Department of Defense. It has also been validated by the National Security Agency as the, “most secure collaboration tool in the world,” says co-founder and CTO of Wickr, Chris Howell. He adds, “Our government and enterprise customers choose Wickr because we have the most secure, end-to-end encrypted platform on the market that enables sensitive mission and business communications without compromising compliance.”Wickr’s largest user base is in the US, followed by Europe, India and Australia, but it has seen an uptick in both their consumer and commercial platforms ever since WhatsApp announced plans to update its privacy policy, says Howell.While the app can be deployed by organisations in highly regulated industries such as banking, energy, healthcare and the federal government, one of its versions, Wickr Me, is more suitable for one-on-one conversations with family and friends. Wickr cannot identify owners because it doesn’t have access to any personal information. The data is encrypted and not accessible to the company. All the messages are stored on the user’s device and for a brief period on Wickr’s servers, but get deleted upon delivery. Since messages are end-to-end encrypted, even when messages are on the server, they are not available to the company.With Wickr Me, users can share files, photos, videos and voice messages, and also do video and audio conferencing. The messages are ephemeral, meaning they only exist for a limited amount of time and get permanently deleted from the sending as well as the receiving device after a while. Therefore, if the recipient doesn’t check Wickr frequently, the messages may never get delivered. “Wickr’s security architecture and proprietary encryption methodology is designed to ensure that only users can gain access to their message content. Users’ content is encrypted locally on their device and is accessible only to intended recipients,” explains Howell.Jami

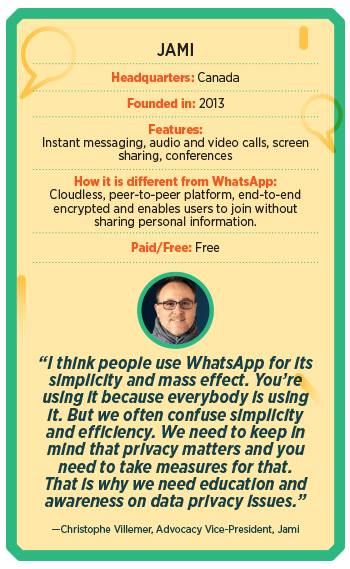

An open-source service, Jami doesn’t store users’ personal information on a central server, guaranteeing users full anonymity and privacy. Around since 2013, Christophe Villemer, advocacy vice-president of the Canada-based messenger app, says, “We really are a newcomer in the market, we estimate there are around 100,000 users around the globe but our community is growing every day.” He says Jami is peer-to-peer, which means it doesn’t require a server for relaying data between users. Therefore, users don’t have to worry about a third party conserving their video or data on its servers. With features such as HD video calling, instant and voice messaging, and file sharing, the service is free to use. All the connections are end-to-end encrypted. “At Jami, we think that privacy is a primary right on the internet. Everybody should be free not to give their data to corporations to benefit from an essential service on the internet,” says Villemer. “Also, we think that our solution, as it’s peer-to-peer, is globally better for the environment because it does not rely on huge server farms or data-centers,” he adds. Users of the service have no restrictions in terms of the size of the files they share, nor speed, bandwidth, features, number of accounts or storage. In addition, if users are on the same local network, they can communicate using Jami even if they are disconnected from the internet. “There will never be advertising on Jami,” says Villemer.Briar

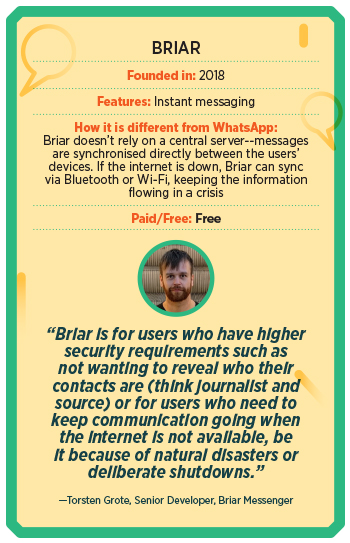

Briar Messenger is a not-for-profit organisation that started off as a project by Michael Rogers in an attempt to support freedom of expression, freedom of association, and the right to privacy. In India, Briar is extremely popular in Kashmir. Reason? It can work without the internet via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. Launched in 2018, this application uses direct, encrypted connections to prevent surveillance and censorship. Briar allows users to form private groups (with one admin that can invite others), write blogs, and also create public discussion forums. The application doesn’t rely on central servers and sends across messages without leaking metadata.Torsten Grote, senior developer, Briar Messenger, says, “Briar is for users who have higher security requirements such as not wanting to reveal who their contacts are (think journalist and source) or for users who need to keep the communication going when the internet is not available, be it because of natural disasters or deliberate shutdowns.” So far, Briar has around 200,000 downloads on Google Play and around 100,000 downloads from their website. The application is also available on F-Droid and other independent stores, which don’t track downloads. However, “thanks to the WhatsApp policy change,” says Grote, “we are seeing 7x the usual number of downloads.”Threema

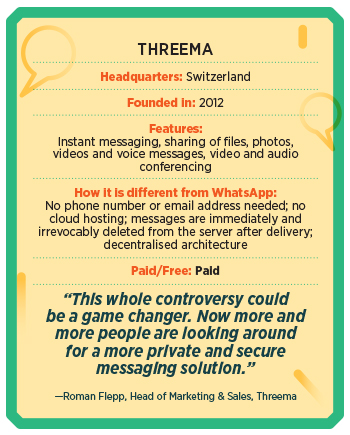

In 2012, three young software developers from Switzerland decided to create a secure instant messenger that would prevent the misuse of user data by companies and surveillance by governments. After Facebook bought WhatsApp in early 2014, the number of users climbed to 2 million in just a few weeks. “In Threema, all communication is protected in the best possible way by end-to-end encryption. Since Threema is open source, users can independently verify that Threema doesn’t have access to any user data that could be handed over to third parties,” says Roman Flepp, head of marketing and sales, Threema.One of Threema’s guiding principles is “metadata restraint”, which means if there is no data, no data can be misused, either by corporations, hackers or surveillance authorities. Currently, the messenger has over 9 million users. In the light of the recent WhatsApp privacy issue, Flepp claims the daily download numbers have increased significantly, by a factor of 10. This growth has been consistently high since the policy change was announced. He adds, “This whole controversy could be a game changer. Now more and more people are looking around for a more private and secure messaging solution.”The application can be used not only by individual users, but also businesses. Threema has various business solutions such as Threema Work and Threema Education. “Especially in the business environment, it is crucial that a secure and privacy-compliant solution is used for work-related communication. We see a great demand, more than 5,000 companies are already using our business solution Threema Work,” says Flepp. Currently, the team is working on creating a multi-device solution that will allow users to use Threema on multiple devices.****While a bunch of these applications are great options for secure peer-to-peer messaging, it is not a very sustainable revenue model for most of these companies. Hence, a few of them have moved to offer enterprise solutions. “For business use, a consumer-focused messaging app [like WhatsApp] is insufficient because it isn’t designed with business requirements for security, privacy, and compliance in mind,” says Shey.Post the recent announcement about the policy changes, a lot of government organisations and companies banned the use of applications like WhatsApp on company-issued devices and for work. We take a look at some applications that offer paid messaging solutions to businesses.Wire

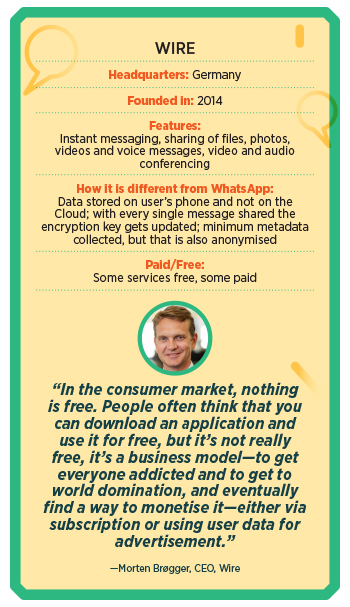

Though the idea for Wire was conceived in 2012, the product was only launched in 2014 and initially for consumers. However, in 2017, the Germany-based company decided to focus mainly on enterprises. This was because, says Morten Brøgger, CEO of Wire, “We were against giants like Facebook, and consumers were not willing to understand the importance of privacy and pay for it.” This was also around the same time that the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) was coming up, and privacy was becoming a major concern for organisations. “Hence, we felt the solution we built would be extremely compelling to enterprise consumers,” he adds.Currently, Wire has close to 1,800 paid customers, which mainly include governments and large enterprises, whereas, for the general free solution, they have about half a million monthly active users. Most of their paid customers are in Germany, North America, Australia, the Middle East, and some European countries.Most of the traditional enterprise SaaS solutions have a few risk points, including “man in the middle vulnerability” since the cloud provider is in the middle, which means all the processing and storage happens on the cloud. The main weakness here is that the cloud provider can technically access the encryption key, which means the cloud provider can technically read and listen to all your content. However, Wire has a very different architecture, wherein there is no man in the middle. “All the data resides in the application on your device. There is some storage on the cloud, for bigger files, and these are secured with individual encryption keys. But the encryption keys only exist on the devices of our users, there’s no copy of the keys on the cloud,” Brøgger says.Another USP of this open-source application is that every time you send or receive a message—be it a text message, call, video conference or screen share—the encryption key updates, hence giving each individual message a unique encryption key. Says Brøgger, “We don’t know who the users are, what they are using it for and we barely collect any metadata, whatever little is collected to help synchronise different devices is also anonymised.”Currently, the company is going at 400 percent revenue growth year-on-year. “We saw a great spike in the paid clients at the beginning of the pandemic, and now [due to the WhatsApp privacy policy issue] since enterprises are becoming more aware of the importance of privacy.”Troop

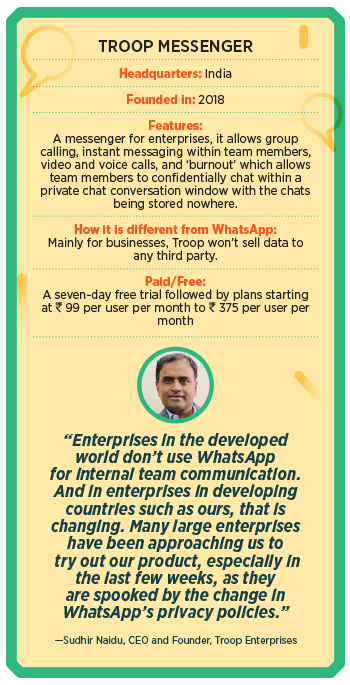

Troop Messenger was launched in mid-2018 as an internal messaging app for enterprises. “It is a home-grown, made in India, robust and a secured business messaging platform,” says CEO and founder Sudhir Naidu. A single platform, it enables internal teams to chat, make audio and video calls, convert them into conferencing, share screens, and create groups. It also features a self-destructible chat window to exchange secured information, and will shortly introduce an email client so users can both send e-mails and messages. “We have pledged that we would not sell any kind of user data to any third-party organisations. We assess and track all kinds of intrusions and attacks and follow the policy of honestly disclosing to clients if there is a breach which involves a threat to their data,” says Naidu. Additionally, Troop follows a stringent and comprehensive internal security framework and policy, in terms of development, testing and release.Besides Indian enterprises, Troop Messenger has been seeing good traction from the US, UK and the Middle East, informs Naidu. “We see three times the usual daily registrations for our platform, since the [WhatsApp] policy came out,” he says. “Businesses that were using WhatsApp before are actively looking out for much safer and business-oriented platforms such as ours,” he adds.Arattai

Zoho Corp, which has products like Zoho Mail and Zoho Business Suite, released a beta version of its messaging application Arattai, meaning chit-chat in Tamil, in the middle of the pandemic in 2020. “More than 70,000 users have already downloaded Arattai and we didn’t advertise at all,” says Praval Singh, VP, marketing at Zoho Corp. “The final application is close to being launched,” he adds. As a privately held company, Singh says, their focus is on user privacy. “We have retained that we’ve held that stance in many ways for our enterprise and business users. And we would like to take it forward with consumer applications as well. For example, we don’t use our own application or data of users to share with third parties, either as a monetisation strategy or for any other reason. So, data that sits on an application doesn’t go to a third party,” he says. In fact, they own their data centers. Therefore, they are not dependent on any third party or public clouds for storage. Spike

Initially released in October 2018, Spike is a conversational and collaborative email application that turns legacy email into a synchronic chat-like experience, adding tasks, collaborative notes and multimedia to create a single feed for work.Instead of using another application, Spike turns an individual’s email address inbox into a hub for chatting with co-workers, friends, and family–as well as a place to work on documents, manage tasks, and share files. Unlike WhatsApp groups, says Dvir Ben-Aroya, co-founder and CEO of Spike, “Spike groups provide a real-time collaborative tool for businesses, without switching between separate team messenger apps.” The application promises to store minimum data to provide fast communication and ensure privacy. Currently, Spike has over 100,000 active teams using this application.“We’ve seen a drastic uptick in users after the WhatsApp announcement, but since we track minimal user data, we cannot access specific data or directly attribute these users’ behaviour with correlation to using WhatsApp,” he says. Its highest user base is in the US, Germany, the UK, and it is very popular in India, especially among students and educators.(With inputs from Namrata Sahoo)

Signal Is Finally Bringing Its Secure Messaging to the Masses

Signal Is Finally Bringing Its Secure Messaging to the Masses

Last month, the cryptographer and coder known as Moxie Marlinspike was getting settled on an airplane when his seatmate, a Midwestern-looking man in his sixties, asked for help. He couldn’t figure out how to enable airplane mode on his aging Android phone. But when Marlinspike saw the screen, he wondered for a moment if he was being trolled: Among just a handful of apps installed on the phone was Signal.

Marlinspike launched Signal, widely considered the world’s most secure end-to-end encrypted messaging app, nearly five years ago, and today heads the nonprofit Signal Foundation that maintains it. But the man on the plane didn’t know any of that. He was not, in fact, trolling Marlinspike, who politely showed him how to enable airplane mode and handed the phone back.

„I try to remember moments like that in building Signal,“ Marlinspike told WIRED in an interview over a Signal-enabled phone call the day after that flight. „The choices we’re making, the app we’re trying to create, it needs to be for people who don’t know how to enable airplane mode on their phone,“ Marlinspike says.

Marlinspike has always talked about making encrypted communications easy enough for anyone to use. The difference, today, is that Signal is finally reaching that mass audience it was always been intended for—not just the privacy diehards, activists, and cybersecurity nerds that formed its core user base for years—thanks in part to a concerted effort to make the app more accessible and appealing to the mainstream.

That new phase in Signal’s evolution began two years ago this month. That’s when WhatsApp cofounder Brian Acton, a few months removed from leaving the app he built amid post-acquisition clashes with Facebook management, injected $50 million into Marlinspike’s end-to-end encrypted messaging project. Acton also joined the newly created Signal Foundation as executive chairman. The pairing up made sense; WhatsApp had used Signal’s open source protocol to encrypt all WhatsApp communications end-to-end by default, and Acton had grown disaffected with what he saw as Facebook’s attempts to erode WhatsApp’s privacy.

Since then, Marlinspike’s nonprofit has put Acton’s millions—and his experience building an app with billions of users—to work. After years of scraping by with just three overworked full-time staffers, the Signal Foundation now has 20 employees. For years a bare-bones texting and calling app, Signal has increasingly become a fully featured, mainstream communications platform. With its new coding muscle, it has rolled out features at a breakneck speed: In just the last three months, Signal has added support for iPad, ephemeral images and video designed to disappear after a single viewing, downloadable customizable „stickers,“ and emoji reactions. More significantly, it announced plans to roll out a new system for group messaging, and an experimental method for storing encrypted contacts in the cloud.

„The major transition Signal has undergone is from a three-person small effort to something that is now a serious project with the capacity to do what is required to build software in the world today,“ Marlinspike says.

Many of those features might sound trivial. They certainly aren’t the sort that appealed to Signal’s earliest core users. Instead, they’re what Acton calls „enrichment features.“ They’re designed to attract normal people who want a messaging app as multifunctional as WhatsApp, iMessage, or Facebook Messenger but still value Signal’s widely trusted security and the fact that it collects virtually no user data. „This is not just for hyperparanoid security researchers, but for the masses,“ says Acton. „This is something for everyone in the world.“

Even before those crowdpleaser features, Signal was growing at a rate most startups would envy. When WIRED profiled Marlinspike in 2016, he would confirm only that Signal had at least two million users. Today, he remains tightlipped about Signal’s total user base, but it’s had more than 10 million downloads on Android alone according to the Google Play Store’s count. Acton adds that another 40 percent of the app’s users are on iOS.

Its adoption has spread from Black Lives Matters and pro-choice activists in Latin America to politicians and political aides—even noted technically incompetent ones like Rudy Giuliani—to NBA and NFL players. In 2017, it appeared in the hacker show Mr. Robot and political thriller House of Cards. Last year, in a sign of its changing audience, it showed up in the teen drama Euphoria.

Identifying the features mass audiences want isn’t so hard. But building even simple-sounding enhancements within Signal’s privacy constraints—including a lack of metadata that even WhatsApp doesn’t promise–can require significant feats of security engineering, and in some cases actual new research in cryptography.

Take stickers, one of the simpler recent Signal upgrades. On a less secure platform, that sort of integration is fairly straightforward. For Signal, it required designing a system where every sticker „pack“ is encrypted with a „pack key.“ That key is itself encrypted and shared from one user to another when someone wants to install new stickers on their phone, so that Signal’s server can never see decrypted stickers or even identify the Signal user who created or sent them.

Signal’s new group messaging, which will allow administrators to add and remove people from groups without a Signal server ever being aware of that group’s members, required going further still. Signal partnered with Microsoft Research to invent a novel form of „anonymous credentials“ that let a server gatekeep who belongs in a group, but without ever learning the members‘ identities. „It required coming up with some innovations in the world of cryptography,“ Marlinspike says. „And in the end, it’s just invisible. It’s just groups, and it works like we expect groups to work.“

Signal is rethinking how it keeps track of its users‘ social graphs, too. Another new feature it’s testing, called „secure value recovery,“ would let you create an address book of your Signal contacts and store them on a Signal server, rather than simply depend on the contact list from your phone. That server-stored contact list would be preserved even when you switch to a new phone. To prevent Signal’s servers from seeing those contacts, it would encrypt them with a key stored in the SGX secure enclave that’s meant to hide certain data even from the rest of the server’s operating system.

That feature might someday even allow Signal to ditch its current system of identifying users based on their phone numbers—a feature that many privacy advocates have criticized, since it forces anyone who wants to be contacted via Signal to hand out a cell phone number, often to strangers. Instead, it could store persistent identities for users securely on its servers. „I’ll just say, this is something we’re thinking about,“ says Marlinspike. Secure value recovery, he says, „would be the first step in resolving that.“

With new features comes additional complexity, which may add more chances for security vulnerabilities to slip into Signal’s engineering, warns Matthew Green, a cryptographer at Johns Hopkins University. Depending on Intel’s SGX feature, for instance, could let hackers steal secrets the next time security researchers expose a vulnerability in Intel hardware. For that reason, he says that some of Signal’s new features should ideally come with an opt-out switch. „I hope this isn’t all or nothing, that Moxie gives me the option to not use this,“ Green says.

But overall, Green says he’s impressed with the engineering that Signal has put into its evolution. And making Signal friendlier to normal people only becomes more important as Silicon Valley companies come under increasing pressure from governments to create encryption backdoors for law enforcement, and as Facebook hints that its own ambitious end-to-end encryption plans are still years away from coming to fruition.

„Signal is thinking hard about how to give people the functionality they want without compromising privacy too much, and that’s really important,“ Green adds. „If you see Signal as important for secure communication in the future—and possibly you don’t see Facebook or WhatsApp as being reliable—then you definitely need Signal to be usable by a larger group of people. That means having these features.“

Brian Acton doesn’t hide his ambition that Signal could, in fact, grow into a WhatsApp-sized service. After all, Acton not only founded WhatsApp and helped it grow to billions of users, but before that joined Yahoo in its early, explosive growth days of the mid-1990s. He thinks he can do it again. „I’d like for Signal to reach billions of users. I know what it takes to do that. I did that,“ says Acton. „I’d love to have it happen in the next five years or less.“

That wild ambition, to get Signal installed onto a significant fraction of all the phones on the planet, represents a shift—if not for Acton, then for Marlinspike. Just three years ago, Signal’s creator mused in an interview with WIRED that he hoped Signal could someday „fade away,“ ideally after its encryption had been widely implemented in other billion-user networks like WhatsApp. Now, it seems, Signal hopes to not merely influence tech’s behemoths, but to become one.

But Marlinspike argues that Signal’s fundamental aims haven’t changed, only its strategy—and its resources. „This has always been the goal: to create something that people can use for everything,“ Marlinspike says. „I said we wanted to make private communication simple, and end-to-end encryption ubiquitous, and push the envelope of privacy-preserving technology. This is what I meant.“

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/signal-encrypted-messaging-features-mainstream/

one of the key things that set SIGNAL MESSENGER apart—that it collects almost no information about its users, appears to be changing.

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/pkyzek/signal-new-pin-feature-worries-cybersecurity-experts

Signal’s New PIN Feature Worries Cybersecurity Experts

The popular encrypted app is now going to store your contacts in the cloud. Experts are worried this compromises users’ privacy.

by Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai

July 10, 2020, 2:33pm

Ever since NSA leaker Edward Snowden said “use Signal, use Tor,” the end-to-end encrypted chat app has been a favorite of people—including Motherboard—who care about privacy and need a chat and calling app that is hard to spy on.

One of the reasons security experts recommended Signal is because the app’s developers collected—and thus retained—almost no information about its users. This means that, if subpoenaed by law enforcement, Signal would have essentially nothing to turn over. Signal demonstrated this in 2016, when it was subpoenaed by a court in Virginia. „We’ve designed the Signal service to minimize the data we retain about Signal users, so the only information we can produce in response to a request like this is the date and time a user registered with Signal and the last date of a user’s connectivity to the Signal service,“ Signal wrote at the time.

But a newly added feature that allows users to recover certain data, such as contacts, profile information, settings, and blocked users, has led some high-profile security experts to criticize the app’s developers and threaten to stop using it. Signal will store that data on servers the company owns, protected by a PIN that the app has initially been asking users to add, and then forced them to.

The purpose of using a PIN is, in the near future, to allow Signal users to be identified by a username, as opposed to their phone number, as Signal founder Moxie Marlinspike explained on Twitter (as we’ve written before, this is a laudable goal; tying Signal to a phone number has its own privacy and security implications).

”Make the networks dumb and the clients smart.”

But this also means that unlike in the past, Signal now retains certain user data, something that many cybersecurity and cryptography experts see as too dangerous.

Matthew Green, a cryptographer and computer science professor at Johns Hopkins University, said that this was “the wrong decision,” and that forcing users to create a PIN and use this feature would force him to stop using the app.

“The problem with that is that most people pick weak PIN codes. To harden this and make the system more secure, Signal has a system that uses Intel SGX enclaves on their server,”Green said in an email to Motherboard, referring to a technology made by Intel to encrypt and isolate certain data on a cloud server. “SGX seems like a good choice, but it really can’t stand up against a serious attacker. This means anyone with the right resources (at least as good as, say, Daniel Genkin’s group and U. Mich) could potentially compromise those servers and get most of this information.”

“I don’t care that much about my contact lists, honestly. But I also don’t like the idea that I’m going to be forced into uploading them to a server, when the whole reason I use Signal is because it’s designed not to do things like this. Also, I’m scared that in the future, Moxie will design a feature to upload message content, and that won’t be ‚opt in‘ either,“ Green said.

Have you ever tried to hack Signal or look for vulnerabilities in the app? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, you can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzofb@vice.com

The Grugq, a well-known cybersecurity expert, agreed that this approach isn’t secure, because SGX enclaves are “a sort of wet paper bag for clustering sensitive info.”

Technical issues aside, it’s the philosophy behind it that bothers people like Green and The Grugq. Before this new feature, Signal claimed—and had proved—to provide a communication app that was designed not to store almost any information about its users.

„Notably, things we don’t have stored include anything about a user’s contacts (such as the contacts themselves, a hash of the contacts, any other derivative contact information), anything about a user’s groups (such as how many groups a user is in, which groups a user is in, the membership lists of a user’s groups), or any records of who a user has been communicating with,“ Signal wrote in 2016.

That, according to critics, has now changed.

“They should have a dumb network that knows nothing because it can’t be compromised then,” The Grugq told Motherboard. “[Having contacts] is a lot. It isn’t messages, sure. But I don’t like it. I don’t want them to have anything. Make the networks dumb and the clients smart.”

Marlinspike defended the decision to enable PINs and give users a way to migrate to a new device and keep certain data, and will increase the security of users’ metadata, “new features Signal users have been asking for.”

“The purpose of PINs is to enable upcoming features like communicating without sharing your phone number. When that is released, your Signal contacts won’t be able to live in the address book on your phone anymore, since they may not have phone numbers associated with them,” Marlinspike told Motherboard. “For most users, this also increases the security of their metadata. Most people’s address book is syncing with Google or Apple, so this change will prevent Google and Apple from having access to your Signal contacts.”

Following Green’s and others critiques, Marlinspike said on Twitter, and then confirmed with us, that Signal will add the ability to disable PINs “for some advanced users.’ Marlinspike warned that doing that “would mean that every time you re-install Signal you will lose all your Signal contacts.”

In recent weeks, Signal has introduced more features that make it more user friendly to people who may not have extremely paranoid threat models. For example, it’s now possible to migrate all Signal data, including message history, from one phone to another, using a feature that does not rely on cloud servers and is also encrypted, according to Signal. This is a different feature than the one that relies on PINs, but both of these are likely aimed at people who may be reluctant to use Signal, and prefer other apps such as WhatsApp.

The changes Signal has made show how there can be a tension between messenger usability and feature set and security. It’s too early to say whether you should stop using the messenger. For most users‘ threat models, it’s still one of the best options. But one of the key things that set Signal apart—that it collects almost no information about its users, appears to be changing.

Secure your Privacy – HERE’S WHY YOU SHOULD USE SIGNAL

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/ditch-all-those-other-messaging-apps-heres-why-you-should-use-signal/

STOP ME IF you’ve heard this before. You text a friend to finalize plans, anxiously awaiting their reply, only to get a message from them on Snapchat to say your latest story was hilarious. So, you move the conversation over to Snapchat, decide to meet up at 10:30, but then you close the app and can’t remember if you agreed on meeting at Hannegan’s or that poppin‘ new brewery downtown. You can’t go back and look at the message since Snapchat messages have a short shelf life, so you send a text, but your friend has already proven to be an unreliable texter. You’d be lucky if they got back to you by midnight.

All of this illustrates a plain truth. There are just too many messaging apps. As conversations can bounce between Snapchat, iMessage, Skype, Instagram, Twitter, and Hangouts/Allo or whatever Google’s latest attempt at messaging is, they’re rendered confusing and unsearchable. We could stick to SMS, but it’s pretty limited compared to other options, and it has some security holes. Rather than just chugging along with a dozen chat apps, letting your notifications pile up, it’s time to pick one messaging app and get all of your friends on board. That way, everyone can just pick up their phones and shoot a message to anyone without hesitation.

Here comes the easy part. There’s one messaging app we should all be using: Signal. It has strong encryption, it’s free, it works on every mobile platform, and the developers are committed to keeping it simple and fast by not mucking up the experience with ads, web-tracking, stickers, or animated poop emoji.

Tales From the Crypto

Signal looks and works a lot like other basic messaging apps, so it’s easy to get started. It’s especially convenient if you have friends and family overseas because, like iMessage and WhatsApp, Signal lets you sidestep expensive international SMS fees. It also supports voice and video calls, so you can cut out Skype and FaceTime. Sure, you don’t get fancy stickers or games like some of the competition, but you can still send pictures, videos, and documents. It’s available on iOS, Android, and desktop.

But plenty of apps have all that stuff. The thing that actually makes Signal superior is that it’s easy to ensure that the contents of every chat remain private and unable to be read by anyone else. As long as both parties are using the app to message each other, every single message sent with Signal is encrypted. Also, the encryption Signal uses is available under an open-source license, so experts have had the chance to test and poke the app to make sure it stays as secure as what’s intended.

If you’re super concerned about messages being read by the wrong eyes, Signal lets you force individual conversations to delete themselves after a designated amount of time. Signal’s security doesn’t stop at texts. All of your calls are encrypted, so nobody can listen in. Even if you have nothing to hide, it’s nice to know that your private life is kept, you know, private.

WhatAbout WhatsApp

Yes, this list of features sounds a lot like WhatsApp. It’s true, the Facebook-owned messaging app has over a billion users, offers most of the same features, and even employs Signal’s encryption to keep chats private. But WhatsApp raises a few concerns that Signal doesn’t. First, it’s owned by Facebook, a company whose primary interest is in collecting information about you to sell you ads. That alone may steer away those who feel Facebook already knows too much about us. Even though the content of your WhatsApp messages are encrypted, Facebook can still extract metadata from your habits, like who you’re talking to and how frequently.

Still, if you use WhatsApp, chances are you already know a lot of other people who are using it. Getting all of them to switch to Signal is highly unlikely. And you know, that’s OK—WhatsApp really is the next-best option to Signal. The encryption is just as strong, and while it isn’t as cleanly stripped of extraneous features as Signal, that massive user base makes it easy to reach almost anyone in your contact list.

Chat Heads

While we’re talking about Facebook, it’s worth noting that the company’s Messenger app isn’t the safest place to keep your conversations. Aside from all the clutter inside the app, the two biggest issues with Facebook Messenger are that you have to encrypt conversations individually by flipping on the „Secret Conversations“ option (good luck remembering to do that), and that anyone with a Facebook profile can just search for your name and send you a message. (Yikes!) There are too many variables in the app, and a lot the security is out of your hands. iMessage may seem like a solid remedy to all of these woes, but it’s tucked behind Apple’s walled iOS garden, so you’re bound to leave out your closest friends who use Android devices. And if you ever switch platforms, say bye-bye to your chat history.

Signal isn’t going to win a lot of fans among those who’ve grown used to the more novel features inside their chat apps. There are no stickers, and no animoji. Still, as privacy issues come to the fore in the minds of users, and as mobile messaging options proliferate, and as notifications pile up, everyone will be searching for a path to sanity. It’s easy to invite people to Signal. Once you’re using it, just tap the „invite“ button inside the chat window, and your friend will be sent a link to download the app. Even stubborn people who only send texts can get into it—Signal can be set as your phone’s default SMS client, so the pain involved in the switch is minimal.

So let’s make a pact right now. Let’s all switch to Signal, keep our messages private, and finally put an end to the untenable multi-app shuffle that’s gone on far too long.

Delete Signal’s texts, or the app itself, and virtually no trace of the conversation remains.

Delete Signal’s texts, or the app itself, and virtually no trace of the conversation remains. “The messages are pretty much gone

Suing to See the Feds’ Encrypted Messages? Good Luck

The recent rise of end-to-end encrypted messaging apps has given billions of people access to strong surveillance protections. But as one federal watchdog group may soon discover, it also creates a transparency conundrum: Delete the conversation from those two ends, and there may be no record left.

The conservative group Judicial Watch is suing the Environmental Protection Agency under the Freedom of Information Act, seeking to compel the EPA to hand over any employee communications sent via Signal, the encrypted messaging and calling app. In its public statement about the lawsuit, Judicial Watch points to reports that EPA staffers have used Signal to communicate secretly, in the face of an adversarial Trump administration.

But encryption and forensics experts say Judicial Watch may have picked a tough fight. Delete Signal’s texts, or the app itself, and virtually no trace of the conversation remains. “The messages are pretty much gone,” says Johns Hopkins crypotgrapher Matthew Green, who has closely followed the development of secure messaging tools. “You can’t prove something was there when there’s nothing there.”

End-to-Dead-End

Signal, like other end-to-end encryption apps, protects messages such that only the people participating in a conversation can read them. No outside observer—not even the Signal server that the messages route through—can sneak a look. Delete the messages from the devices of two Signal communicants, and no other unencrypted copy of it exists.

In fact, Signal’s own server doesn’t keep record of even the encrypted versions of those communications. Last October, Signal’s developers at the non-profit Open Whisper Systems revealed that a grand jury subpoena had yielded practically no useful data. “The only information we can produce in response to a request like this is the date and time a user registered with Signal and the last date of a user’s connectivity to the Signal service,” Open Whisper Systems wrote at the time. (That’s the last time they opened the app, not sent or received a message.)

Even seizing and examining the phones of EPA employees likely won’t help if users have deleted their messages or the full app, Green says. They could even do so on autopilot. Six months ago, Signal added a Snapchat-like feature to allow automated deletionof a conversation from both users’ phones after a certain amount of time. Forensic analyst Jonathan Zdziarski, who now works as an Apple security engineer, wrote in a blog post last year that after Signal messages are deleted, the app “leaves virtually nothing, so there’s nothing to worry about. No messy cleanup.” (Open Whisper Systems declined to comment on the Judicial Watch FOIA request, or how exactly it deletes messages.)

Still, despite its best sterilization efforts, even Signal might leave some forensic trace of deleted messages on phones, says Green. And other less-secure ephemeral messaging apps like Confide, which has also become popular among government staffers, likely leave more fingerprints behind. But Green argues that recovering deleted messages from even sloppier apps would take deeper digging than FOIA requests typically compel—so long as users are careful to delete messages on both sides of the conversation and any cloud backups. “We’re talking about expensive, detailed forensic analysis,” says Green. “It’s a lot more work than you’d expect from someone carrying out FOIA requests.”

For the Records

Deleting records of government business from government-issued devices is—let’s be clear—illegal. That smartphone scrubbing, says Georgetown Law professor David Vladeck, would blatantly violate the Federal Records Act. “It’s no different from taking records home and burning them,” says Vladeck. “They’re not your records, they’re the federal government’s, and you’re not supposed to do that.”

Judicial Watch, for its part, acknowledges that it may be tough to dig up deleted Signal communications. But another element of its FOIA request asks for any EPA information about whether it has approved Signal for use by agency staffers. “They can’t use these apps to thwart the Federal Records Act just because they don’t like Donald Trump,” says Judicial Watch president Tom Fitton. “This serves also as an educational moment for any government employees, that using the app to conduct government business to ensure the deletion of records is against the law, and against record-keeping policies in almost every agency.”

Fitton hopes the lawsuit will at least compel the EPA to prevent employees from installing Signal or similar apps on government-issued phones. “The agency is obligated to ensure their employees are following the rules so that records subject to FOIA are preserved,” he says. “If they’re not doing that, they could be answerable to the courts.”

Georgetown’s Vladeck says that even evidence employees have used Signal at all should be troubling, and might warrant a deeper investigation. “I would be very concerned if employees were using an app designed to leave no trace. That’s smoke, if not a fire, and it’s deeply problematic,” he says.

But Johns Hopkins’ Green counters that FOIA has never been an all-seeing eye into government agencies. And he points out that sending a Signal message to an EPA colleague isn’t so different from simply walking into their office and closing the door. “These ephemeral communications apps give us a way to have those face-to-face conversations electronically and in a secure way,” says Green. “It’s a way to communicate without being on the record. And people need that.”

https://www.wired.com/2017/04/suing-see-feds-encrypted-messages-good-luck/