The rebirth of advertisements and AdTech in the age of AI

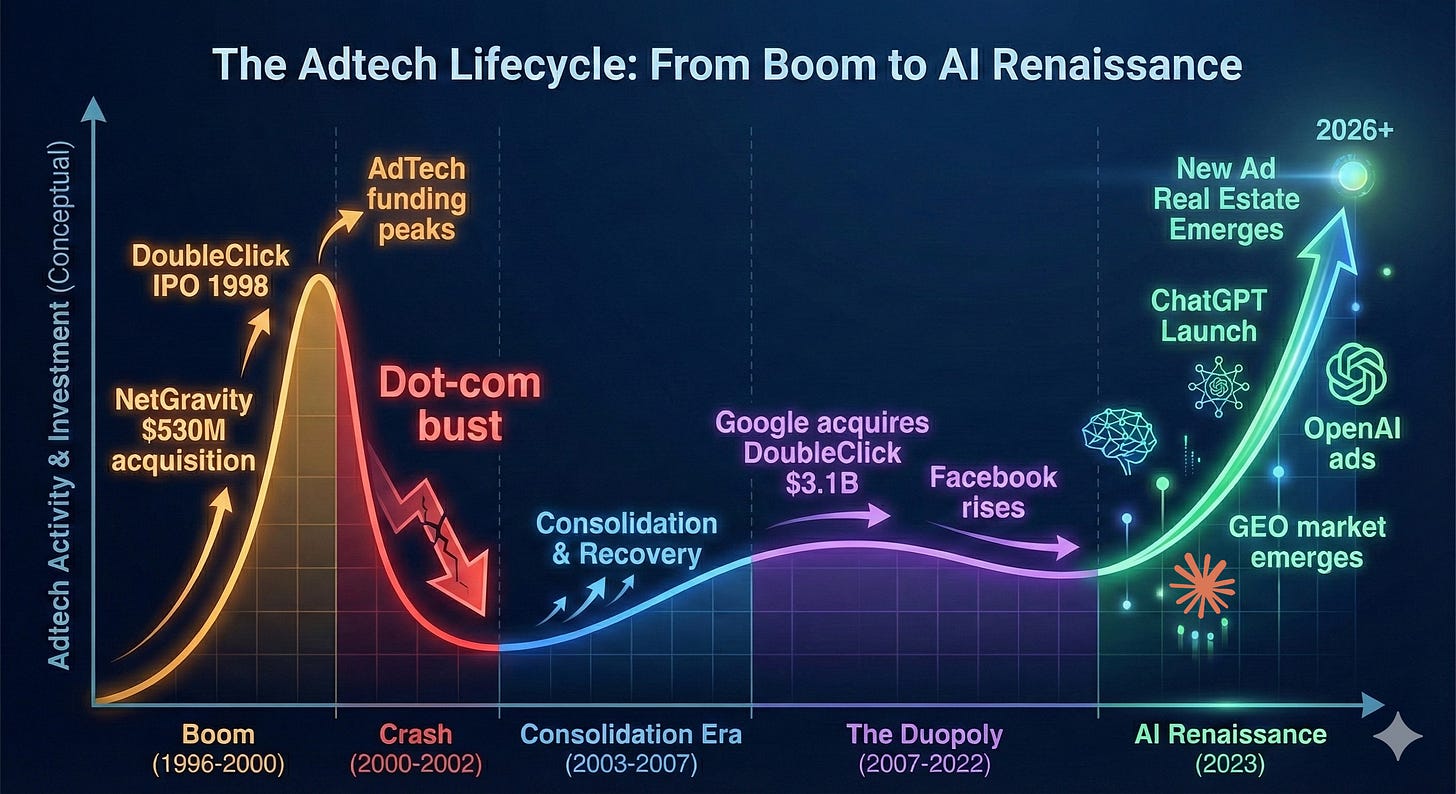

AdTech used to matter. In the early 2000s, it was one of the hottest areas in tech – hundreds of startups, billions in VC funding, genuine innovation in targeting and formats. Then Google bought DoubleClick in 2007 for $3.1 billion, Facebook launched its ad platform, and the game was over. The duopoly that emerged didn’t just dominate—at their peak, Google and Meta controlled nearly 80% of U.S. digital ad growth. Everyone else was left fighting for scraps. For the past 15 years, „AdTech startup“ became practically an oxymoron as the industry consolidated into irrelevance.

But now, in the age of AI, we are starting to see a resurgence of advertising as a booming revenue source for companies. OpenAI announced last week that they would be testing ads in ChatGPT in a “bid to boost revenue”, and the healthcare AI startup OpenEvidence recently surpassed $100M annualized run-rate revenue (and doubled their valuation to $12B!), largely on an ad-supported revenue model. And around this, the market for AI tools in advertising optimization is growing quickly.

So why are we seeing such a sharp resurgence in a field that just a few years ago was essentially dead?

Three fundamental shifts are driving this renaissance:

First, AI platforms have created the first genuinely new advertising surface since social media. ChatGPT’s 800+ million weekly active users and Claude’s ~20 million monthly active users represent massive, engaged audiences that didn’t exist two years ago. Unlike the incremental improvements of the past decade – slightly better targeting, marginally improved attribution – these platforms represent entirely new real estate where the old duopoly rules don’t apply.

Second, intent signals are dramatically more sharply defined than anything we’ve seen before. When someone types “best CRM for startups” into Google, you get a decent intent signal. But when someone has a 20-message conversation with ChatGPT about their specific sales team structure, pain points, budget constraints, and technical requirements? That’s intent data at a resolution advertisers have only dreamed about. The conversational nature of AI interactions creates a richness of context that search queries simply can’t match.

Third, entirely new infrastructure is required—and being built at breakneck speed. The old AdTech stack was built for display ads, search results, and social feeds. None of it works for conversational AI. How do you measure attribution when there’s no “click”? How do you bid on inventory that’s generated dynamically in response to natural language? What does “viewability” even mean in a text-based conversation? This infrastructure gap is spawning entirely new categories like Generative Engine Optimization (GEO), with dozens of startups raising millions to solve problems that didn’t exist 18 months ago.

So should we be heralding the rebirth of AdTech in the age of AI?

Let’s dig in.

AI is Creating New Real Estate for Ads

The rapid growth of foundation models with “chatbot-style interfaces” has brought forward what we believe is the first new real estate for advertisements since the emergence of social networks. Google and Meta were able to establish dominance in ad models by aggregating eyeballs; Google in search and Meta in social. (And to a lesser extent other social media platforms like Snap, Pinterest, etc.). As an advertiser, why would I place my ads anywhere other than where consumers are aggregating to get most bang for my buck?

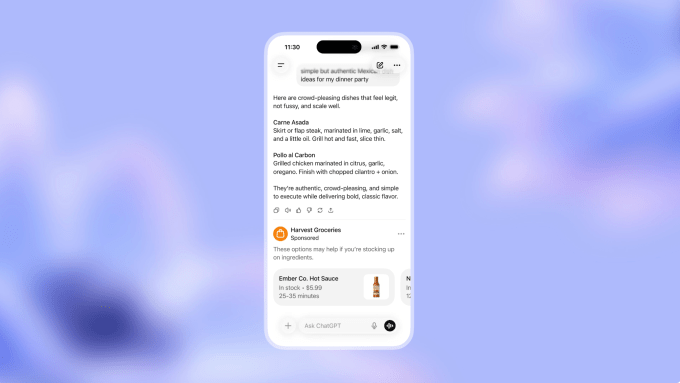

Now in the Age of AI, consumers are no longer flocking to the traditional platforms but increasingly to places like ChatGPT (>800M WAUs) and Claude (~20M MAUs). And these consumers are not just making simple search queries but having full-blown conversations on every topic under the sun. This is an advertiser’s dream: a wide-scale canvas with rich, user-generated intent. And advertisers are no longer limited to traditional search displays with sponsored results but can embed more natural advertisements within AI-generated responses. While the consumer may not love this (more on that below), it certainly makes sense for the advertisers.

Beyond consumer-facing platforms, AI development tools are creating a quieter but equally significant advertising opportunity. When developers use tools like Lovable, Replit, or Cursor to build applications, these platforms make dozens of architectural decisions on their behalf—which database to use, where to host, which payment processor to integrate.

Each of these decisions represents potential advertising inventory. Supabase could sponsor recommendations in database selection flows. Vercel could appear as a ‘suggested deployment option’ when a developer’s app is ready to ship. Stripe could surface contextual offers when payment processing code is being written.

The key difference from traditional developer advertising (think Stack Overflow banner ads) is that these aren’t interruptions—they’re recommendations at the exact moment of intent. A developer isn’t being shown a database ad while reading about React hooks; they’re being offered database options precisely when their AI agent is about to scaffold database code. The conversion potential is orders of magnitude higher.

Vertical AI Is Creating Specialized Inventory

It’s not just the large model providers themselves that are benefiting from ads.

The rise of vertical AI providers is creating a new, specialized inventory for high-intent, high-value ads. Verticals like healthcare, legal, finance, real estate, and other professional services are becoming the new adtech frontier, offering advertisers direct access to high-value audiences outside the Google-Meta duopoly for the first time in over a decade.

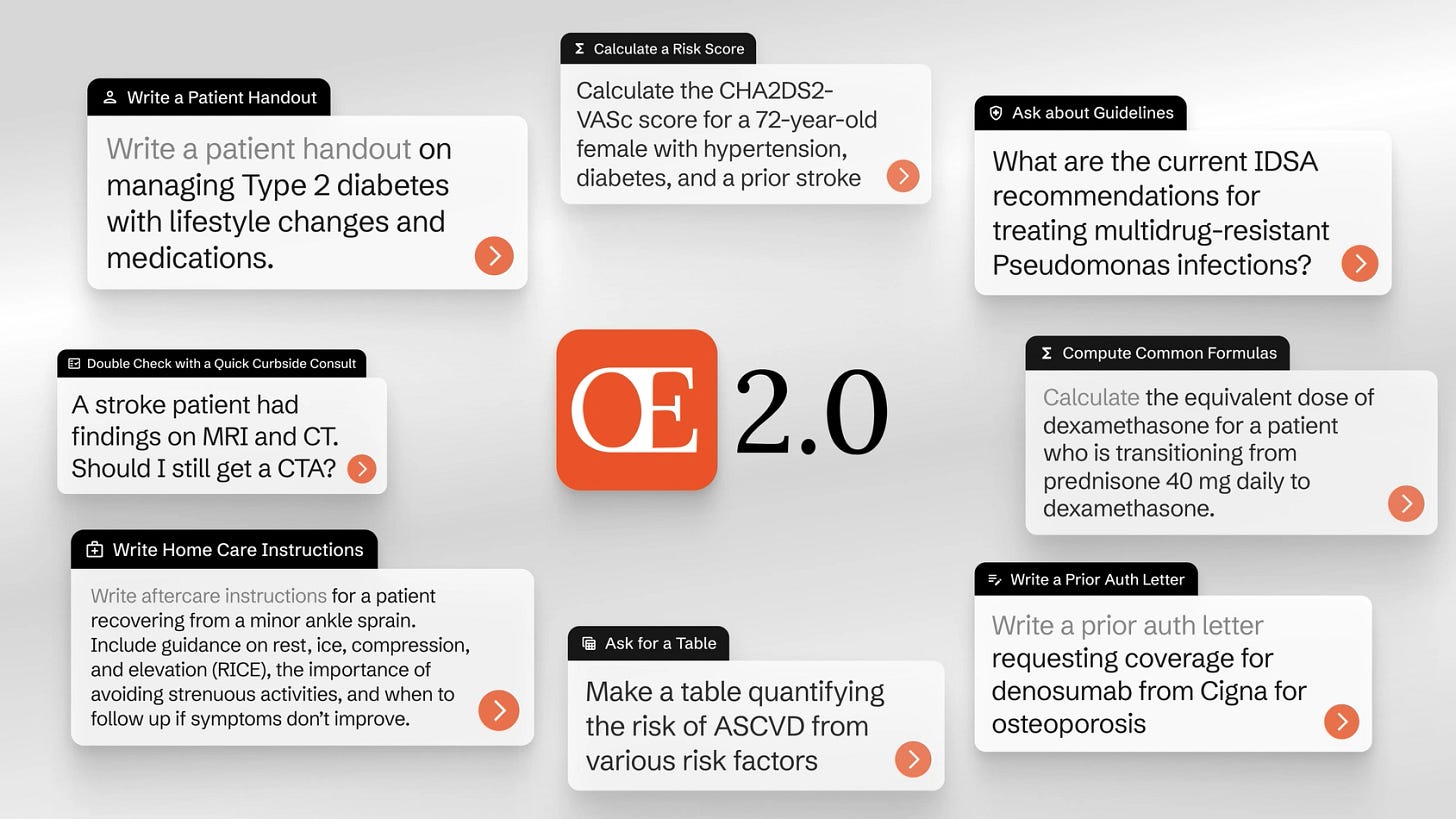

One great example here is OpenEvidence, which has quickly grown into the leading “AI-powered medical search engine” for clinicians. The company recently said that 40% of physicians across the US across 10K hospitals and medical centers now use OpenEvidence on a daily basis. What else is interesting and unique is its business model: OpenEvidence is free to use for verified medical professionals, and generates revenue largely through advertising.

Per a great business breakdown from Contrary Research:

Given that pharmaceutical companies spent approximately $20 billion annually on marketing to healthcare professionals in the US as of 2019, capturing a portion of this market through digital channels could generate substantial revenue for the company. OpenEvidence’s advertising focus on contextual advertising and sponsored content while maintaining trust. For example, if a doctor submits a query about diabetes treatments, a sponsored summary from a pharmaceutical manufacturer may appear, or a banner for relevant clinical webinars could be displayed.

This advertising model has allowed OpenEvidence to reach >$100M annualized run-rate revenue in just a few short years.

We believe that other vertical AI tools will also embed this type of model, giving away the product to end users for free while generating revenue from charging advertisers. In vertical AI, the intent signals are clearer than ever—and unlike the generic search box, users are getting AI agents that actually solve their specific problems, creating a sustainable value exchange that justifies the ad-supported model.

Measurement Primitives are Changing and New Infrastructure is Emerging

Attribution in AI-native experiences is fundamentally different. The old AdTech stack was built for discrete surfaces where ads could be served, clicked, and tracked, but in conversational and agentic interfaces, there’s often no obvious “ad slot” and no click at all. Instead, influence is embedded inside multi-turn workflows: what the model recommends, what the user accepts, and what gets generated.

In next-gen AI apps, advertising is moving into the flow of work. When a developer scaffolds an app in Cursor, Lovable, or Vercel, the inventory isn’t a banner but it’s the moment an agent suggests a database, auth provider, or cloud service. In vertical AI tools, the same pattern holds: the “ad” looks like a contextual recommendation for a pharmaceutical brand, clinical resource, or specialized service. These touchpoints are integrated into the utility itself.

This shift is spawning an entirely new measurement rail. If clicks disappear, the new primitives become telemetry and adoption: logging multi-turn conversations, mapping model outputs to downstream actions, and tracking “acceptance events” like tab-to-insert, install, purchase, or integration. And because influence in a conversation is cumulative, the real challenge isn’t just attribution but it’s incrementality: did the recommendation actually change what the user would have done otherwise?

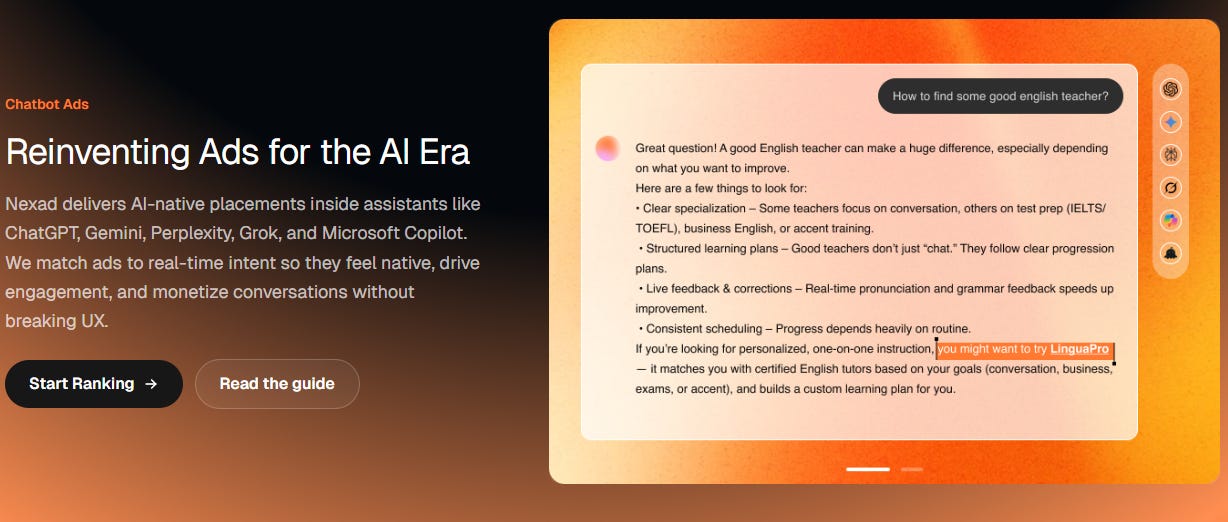

As a result of this shift, we are starting to see new ad networks emerge to serve these “in-flow” moments.

- On the measurement side, companies like Profound and Bluefish are building the GEO observability layer, tracking share-of-response, competitive displacement, and brand presence across models.

- On the distribution side, a new generation of AI-native ad platforms is forming across multiple surfaces: platforms like ZeroClick, OpenAds, and Nex.ad are beginning to monetize dynamic, contextually relevant recommendations inside or alongside AI conversations, while publisher-centric AI engagement platforms like Linotype.ai help site owners retain users and surface native monetization opportunities.

But unlike the old web, the “auction” can’t just pick the highest bidder. It has to operate inside generation loops, ranking units based on contextual relevance, quality, and bid while navigating trust and policy constraints in sensitive domains like healthcare and legal. Pricing models may shift as well, away from CPM/CPC and toward outcomes like cost-per-accept, cost-per-embed, or cost-per-adoption.

The biggest wildcard is walled gardens. If OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and vertical copilots control the interface, they may also control the inventory and measurement rails, turning AI advertising into a handful of closed ecosystems rather than an open programmatic market. Time will tell!

Conclusion / Challenges

There’s one clear challenge in all of this: people generally dislike advertisements. A recent report found that 81% of young people hate ads, and 60% find them intrusive. And who’s to blame them? Most people find ads annoying and not beneficial to them, and now nearly half the internet uses an ad blocker.

Another key challenge is whether people will feel that the answers they are served by the LLMs are influenced by the advertisements that appear. If I ask Claude for the best recommendations for hotels in Switzerland, will I know it showing me what the model says is “best”, or which hotel is spending the most on advertising for this query result?

But here’s the interesting part: in the same study referenced above, only 28% of respondents wanted fewer ads. Which suggests that its not the brands or products being peddled they dislike, but how the ads are actually served.

This could actually be a boon to the new platforms like OpenAI and Anthropic, as well as the emerging AI Adtech tools. By finding creative, non-intrusive, intent-based, transparent, and beneficial ways to reach consumers, a new form of advertising could actually flourish.

So we’re left with the thought…

“Traditional AdTech is Dead…Long Live AdTech For AI“.

Source: https://aspiringforintelligence.substack.com/p/traditional-adtech-is-dead-long-live

When Adele Lowitz, left, experimented with using an Android smartphone instead of an iPhone, one friend asked: ‘Who’s green?’ PHOTO: STEVE KOSS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

When Adele Lowitz, left, experimented with using an Android smartphone instead of an iPhone, one friend asked: ‘Who’s green?’ PHOTO: STEVE KOSS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL How Apple’s iPhone and Apps Trap You in a Walled GardenApple’s hardware, software and services work so harmoniously that it is often called a “walled garden.” The idea is central to recent antitrust scrutiny and the Epic vs. Apple case. WSJ’s Joanna Stern went to a real walled garden to explain it all. Photo illustration: Adele Morgan/The Wall Street Journal

How Apple’s iPhone and Apps Trap You in a Walled GardenApple’s hardware, software and services work so harmoniously that it is often called a “walled garden.” The idea is central to recent antitrust scrutiny and the Epic vs. Apple case. WSJ’s Joanna Stern went to a real walled garden to explain it all. Photo illustration: Adele Morgan/The Wall Street Journal