Ausblick auf eine nicht ganz so schöne neue Welt, in der das technisch Machbare die zentrale Rolle spielen wird.

Ein Herrscher der Welt – oder zumindest einer seiner engsten Mitarbeiter – ist am 26. März in Wien öffentlich aufgetreten. Und nein, es war nicht Barack Obama, auch kein US-Regierungsvertreter, sondern Peter Norvig, Forschungsdirektor bei Google und Experte für intelligente Maschinen. Er war Gast der TU Wien im Rahmen der „Gödel Lectures“, benannt nach dem berühmten österreichischen Mathematiker, der vor den Nazis fliehen musste und seine Karriere in Princeton fortsetzte.

Der große Hörsaal der TU in der Gußhausstraße war zum Bersten voll, mit Hunderten von Lehrpersonen und Informatikstudenten, die alle begierig waren, zu erfahren, wie Computer selbstständig lernen können, ohne von Menschen speziell darauf programmiert zu sein. Wie viele von den Zuhörern in diesem Saal haben davon geträumt, eines Tages für Google zu arbeiten ?

Norvig war nicht im Anzug gekommen, er trug das unorthodoxe Outfit derer, die die Welt revolutionieren wollen: Fünf-Dollar-Hose und farbig getupftes T-Shirt. Es waren nicht nur seine Aussagen, die beeindruckten, sondern auch sein Aussehen.

Bemerkenswert war auch, dass sich der Amerikaner sofort auf das Universum der Science-Fiction berief, ein Genre, welches im deutschen Sprachraum eher als Jugendunterhaltungslektüre verachtet wird. Der Schriftsteller Philip K. Dick (1928-1982) ist beispielsweise weitgehend unbekannt, obwohl er erfolgreiche Hollywoodfilme inspiriert hat.

Zu perfekte Replikanten

Blade Runner (1982), ein Werk des Regisseurs Ridley Scott über einen Polizisten, der zu perfekte Replikanten, die sich unter die Menschen mischen, eliminieren soll, fußt auf einem von Dicks Romanen, ebenso wie Total Recall (1990) von Paul Verhoeven, mit Arnold Schwarzenegger als einem Arbeiter, dem man falsche Erinnerungen implantiert hat. Desgleichen geht Steven Spielbergs Minority Report(2002), eine Filmstory über eine Polizeitruppe, die vorsorglich zukünftige Kriminelle aufspüren und verhaften kann, auf eine Erzählung von Philip K. Dick aus dem Jahr 1956 zurück.

Dick stellte sich vor, dass die Zukunftspolizei sich sogenannter „Precogs“ bedienen könnte, Menschen mit hellseherischen Fähigkeiten. So visionär Dick auch gewesen sein mag, der Kalifornier konnte sich noch nicht die unfassbaren Rechenleistungen der Computer vorstellen. Heute leben wir in einer Welt, die Dick damals zumindest erahnte: In mehreren US- Städten gibt es das System PredPol (Predictive Policing), das mit Google Street View verbunden ist und auf Algorithmen aufbaut, die es der Polizei möglich machen, vorauszusagen, in welchem Viertel einer Stadt Einbrecherbanden oder Plünderer aktiv werden. Pred- Pol wird bald auch nach Europa kommen.

Roboter machen sich in unserem täglichen Leben breit, unser (zukünftiges) Verhältnis zu ihnen ist beispielsweise im Zentrum der schwedischen TV-Serie Real Humans (auf Arte). Haben diese Wesen Rechte? Wird man sich strafbar machen, wenn man sich ihnen gegenüber grausam verhält – wie bei der Misshandlung von Tieren?

Diese Fragen werden die westlichen Juristen und Philosophen beschäftigen, aber es ist in Asien, wo die reale Entwicklung die Debatte entscheiden wird. Die Überalterung der Bevölkerung, der Mangel an Arbeitskräften und an Frauen wegen der selektiven Abtreibung von weiblichen Föten (einer Folge der chinesischen Ein-Kind-Politik) werden immer mehr Substitute erfordern.

Man braucht nur „Yangyang“ anzuschauen, jenen weiblichen Humanoiden, der am 29. April auf der Global Mobile Internet Conference in Peking vorgestellt wurde, „um das junge Publikum für die Robotik anzusprechen“. Nehmen wir diesem von einem Japaner konzipierten und in Schanghai gebauten Roboter die Brillen ab und kleiden wir ihn reizvoll: Dann kann man sich das Potenzial vorstellen, wenn künftig 20 bis 30 Prozent der Männer in China und Indien dem Economist zufolge mangels Partnerinnen zum Zölibat verdammt sein werden …

Norvig ist nicht der Einzige, der in der Science-Fiction stimulierende und beunruhigende Hypothesen findet, wie in dem schönen Film Ex Machina von Alex Garland. Am 1. Mai 2014 haben vier hochkarätige Wissenschafter – die Briten Stephen Hawking (Astrophysiker) und Stuart Russell (Spezialist für künstliche Intelligenz, KI) sowie die Amerikaner Max Tegmark (Kosmologe und Wissenschaftsphilosoph) und Frank Wilczek (Nobelpreisträger für Physik) – anlässlich des Filmstarts von Transcendence in der britischen Tageszeitung The Independent ihre Verwunderung darüber ausgedrückt, dass es völlig an einer öffentlichen Diskussion über die intelligenten Maschinen mangle.

Johnny Depp spielt in Transcendence einen Forscher, dessen Gehirn mit einem Computer verschmilzt, während eine Gruppe „Revolutionäre Unabhängigkeit von Technologie“ (RIFT) subversive Attentate gegen KI-Forschungslabore organisiert. Das Thema des Films ist die „Singularität“: Damit ist der Moment gemeint, zu dem sich eine Maschine mittels künstlicher Intelligenz erstmals selbst verbessern kann. Gerade dieser Singularitätsmoment ist es, der unsere vier Wissenschafter beunruhigt.

„Wenn eine außerirdische Zivilisation uns eine Nachricht senden würde: ,Wir kommen in einigen Jahrzehnten‘, würden wir dann nur antworten: ,Okay, ruft dann an, wir werden das Licht anmachen‘? Wohl nicht. Aber das ist es mehr oder weniger, was mit der künstlichen Intelligenz passiert“, stellen sie fest. Ihnen zufolge wäre die Erfindung von Maschinen, die unsere Intelligenz übersteigen, „das größte Ereignis in der Geschichte der Menschheit. Leider könnte es auch das letzte sein.“

Einer Kirche näher als Nasdaq

Im deutschsprachigen Raum wird die Gegenwart immer vor dem Hintergrund der Vergangenheit interpretiert, d. h. der Naziherrschaft und des Kommunismus. „Stasi-Barbie“, schrieben die deutschen Blätter, als man erfuhr, dass die Firma Mattel Ende 2015 eine vernetzte Puppe auf den Markt bringen wird. Das Problem geht jedoch weit über die ständige Überwachung des Einzelnen, wie von Edward Snowden angeprangert, oder über die kommerzielle Ausbeutung von gesammelten Daten hinaus. Denn Google, das in den nur 17 Jahren seines Bestehens zum mächtigsten Unternehmen der Welt geworden ist, ist viel mehr als eine Firma, die nach Profit strebt: Es ist die Matrix einer Religion der Technologie.

Der Zusammenbruch des kommunistischen Systems hat zu seinem Wachstum wesentlich beigetragen. Es ist nicht mehr der vom Marxismus geforderte Wandel der sozialen Verhältnisse, der zu einer Verbesserung der Gesellschaft beiträgt, auch nicht, wie nach alten humanistischen Idealen, Erziehung und Kultur. Es ist der technische Fortschritt, der die Armut beseitigen, die Umwelt retten, Leid, Krankheit und, warum auch nicht, auch den Tod besiegen soll. „Wenn Sie von religiösem Mythos sprechen“, meint der Anthropologen Eric Guichard, „denken Sie wohl immer an ferne Völker, bei denen man sich unter einem Mangobaum versammelt. Hier haben Sie Megamessen mit Leuten in Anzug und Krawatte“ (oder eben in einem farbig getupften T-Shirt).

In den letzten zwei Jahren hat Google über zehn Spitzenbetriebe der Robotik und der KI gekauft, wie etwa Deep Mind, ein Start-up, das auf sogenanntes Deep Learning spezialisiert ist: das Selbstlernen von Maschinen dank einer dem menschlichen Hirn nachempfundenen IT-Architektur. Die in Mountain View ansässige Firma hat auch Calico gegründet, ein Projekt mit dem Anspruch, die „Grenzen des Todes hinauszuschieben“.

Dieser regelrechte Kaufrausch kommt einem qualitativen Sprung gleich, den die Konkurrenten von Google nicht antizipiert hatten. Einer der wenigen in Frankreich, die das System hinter diesen Übernahmen verstanden haben, ist der Chirurg Laurent Alexandre, der in der Beilage Sciences & Médecine von Le Monde schreibt. Für ihn ist Google „einer Kirche näher als dem Nasdaq“. Alexandre ließe sich schwer in das Lager der Modernisierungsfeinde einordnen: Er ist mit der Medizin-Webseitedoctissimo zu Reichtum gekommen und leitet eine Firma, die sich auf DNA-Sequenzierung spezialisiert hat. Und er ist überzeugt, dass Google sich zum Ziel gesetzt hat, „seine Suchmaschine zur KI hin zu entwickeln“ . Politische Probleme wären dann nicht auszuschließen: Sollte nämlich die Firma die weltweite Führung im Bereich NBIC (Nanotechnologie, Biomedizin, Informatik und Kognitionswissenschaften) übernehmen, „könnte sie mächtiger werden als viele Staaten“.

Dass Ray Kurzweil Ende 2012 zum Gesamtverantwortlichen für die Forschungstätigkeit von Google ernannt wurde, lässt auf die Strategie des Megakonzerns schließen. Mit seinen 67 Jahren ist Kurzweil nicht nur ein genialer Informatiker, ein Pionier der optischen Erkennung von Schriftzeichen, Inhaber so mancher Patente, und Berater amerikanischer Militärs. Kurzweil ist darüber hinaus auch so etwas wie der Papst des Transhumanismus.

Diese in den 1950er-Jahren entstandene Strömung hat lange Zeit kaum mehr Einfluss auf unsere Gesellschaft gehabt als die Rosenkreuzer, auch wenn es von Anfang an nicht an Militanz in den Forschungseinheiten z. B. bei der Nasa oder bei Arpanet, dem Vorfahren des Internets, gemangelt hat. Aber seit die transhumanistische Ideologie die Führungsetage von Google derart beeinflusst, dass diese gar ihren bekanntesten Repräsentanten in eine Schlüsselposition hievt, ändert sich die Perspektive grundlegend.

Kurzweil leitet die „Singularity University“, die von Google und der Nasa finanziert wird: Sie bietet Seminare, die die Eliten der Welt auf den Moment vorbereiten sollen, zu dem Maschinen uns übertreffen werden. Für die Transhumanisten wäre es unnötig, ja sogar gefährlich, sich einer derartigen Entwicklung entgegenzustemmen. Das würde bedeuten, Forschung in den Untergrund zu verbannen, wo deren Ergebnisse von bösen Mächten genutzt werden könnten.

Um dem ungleichen Wettbewerb mit den intelligenten Maschinen standhalten zu können, die die Macht der Zahlen und der Kommunikation im Netz beherrschen, bestehe die einzige Chance der Menschen in ihrer Fähigkeit, ihre eigene Intelligenz zu „steigern“, sei es durch elektronische Implantate, die auf das Gehirn wirken (Google Glass ist ein Prototyp), sei es durch die Beeinflussung der natürlichen Auslese. Das ist das „Bio-Engineering“, das im Westen ethischer Argumente wegen in Verruf steht, jedoch heimlich in den asiatischen Dependancen der technisch-industriellen Galaxie mit enormem Aufwand betrieben wird.

Kein Tabu in China

Es ist wohl kein Zufall, dass ein chinesisches Team in den Medien der ganzen Welt mit der Meldung Schlagzeilen gemacht hat, dass es das genetische Erbgut nicht lebensfähiger Embryonen manipuliert habe. Anfang 2013 hat China mit einer großen Kohorte von Freiwilligen ein Programm zur Sequenzierung der DNA von Hochbegabten gestartet. Der damalige Chef dieses Projektes am Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), das „Wunderkind“ Zhao Bowen, zeigte sich völlig entspannt: Für den Westen, erklärte er dem Wall Street Journal, sei der genetische Anteil an der Intelligenz ein Tabu, nicht jedoch für China.

Bis jetzt ist das fragliche „Gen der Intelligenz“ nicht entdeckt worden. Aber das BGI, ein Freischärler am Rande der offiziellen Wissenschaft (das Institut ist wegen seiner „verrückten“ Ideen aus der chinesischen Akademie der Wissenschaften ausgeschlossen worden, hat aber immerhin ein Viertel der DNA-Analysen des Planeten erzeugt), will ein Labor zukünftiger Entwicklungen sein. Wie sein Vorstand Jian Wang dem Magazin New Yorker sagte: „Sie [der Westen] brauchen, dass jemand das alles sprengt.“ Gemeint waren die lästigen bioethischen Regeln und Protokolle.

Wozu die Veranlagung besonderer Intelligenz besser verstehen, wenn man in der Folge nicht bereit ist, dank der Präimplantationsdiagnostik eine Selektion der Embryonen mit dem besten neurogenetischen Erbgut vorzunehmen? Gerade zu einer Zeit, in der Wissenschafter die Hypothese in den Raum stellen, dass dank des erfolgreichen Kampfs gegen die Säuglingssterblichkeit die Mechanismen zur natürlichen Auslese beim Menschen allmählich abnehmen, gerade in einer solchen Zeit wäre die Versuchung groß, unsere Spezies auf anderem Weg zu verbessern. Schließlich sind wir einem unbarmherzigen Wettbewerb mit den intelligenten Maschinen ausgesetzt.

Menschheit 2.0 ist der Titel des letzten Buches von Kurzweil, der mit Prognosen nie gegeizt hat. Eine typisch transhumanistische Sorge, „den Tod zu euthanasieren“, scheint daher nur sinnvoll. Wozu zig Milliarden Dollar investieren, um das menschliche Hirn zu verbessern, wenn man ohnehin mit 65 an Krebs oder mit 85 durch Schlaganfall stirbt?

Kurzweil und Sergey Brin, einer der beiden Erfinder von Google neben Larry Page, haben den Tod herausgefordert. Brin weiß, dass er genetisch für Parkinson prädisponiert ist. Seine Frau, die Biologin Anne Wojcicki, hat 23andMe gegründet, eine Firma für Gentests. Diese gehört zu Google Life Sciences, die heute ein Drittel des Forschungsbudgets der Firma beansprucht und Verträge mit dem Pharmariesen Novartis geschlossen hat. Kurzweil und Brin setzen voll auf „Nano-Bots“: Unsichtbar gemacht, um den Antikörpern zu entgehen, werden sie sich in unserem Körper tummeln, wie die Miniaturmediziner in derFantastischen Reise (1966), dem Science-Fiction-Film von Richard Fleischer.

Für die Anthropologin Daniela Cerqui von der Universität Lausanne, die seit Jahren über die Mensch-Maschine-Hybridisierung nachdenkt, wird die praktisch grenzenlose Erweiterung der therapeutischen Anwendung dank der NBIC vor allem die Chancenungleichheit beim Zugang zur Medizin verstärken. Und die Idee, „dass man nichts zu ändern braucht außer uns selbst“, verfestigen.

Wir sollten uns auf eine mögliche Allianz von Google und China gefasst machen. China, ein Fünftel der Weltbevölkerung, ist das einzige Beispiel einer sehr alten Zivilisation, die niemals das Konzept der Transzendenz gekannt hat: Religiöse Überlegungen spielen keine Rolle, nur Ordnung und Harmonie zählen, beide werden heute mit eiserner Hand vom kommunistischen Staat gesichert. Wenn die Entscheidung an der Staatsspitze getroffen würde, den Weg der Menschheit 2.0 zu beschreiten, wird es dazu kommen.

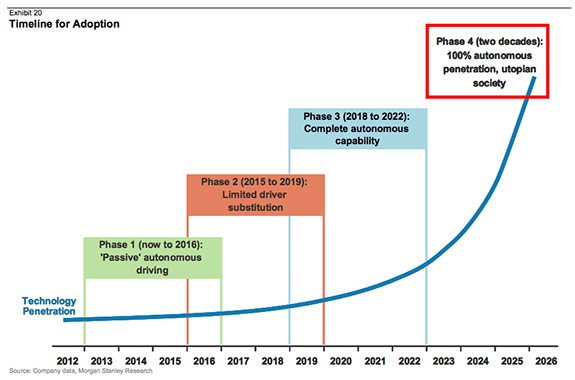

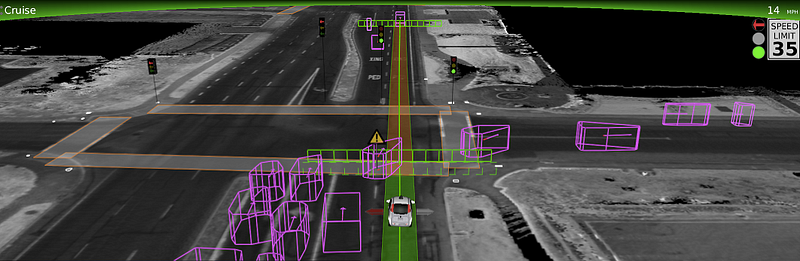

Man beginnt erst allmählich, die Auswirkungen des allgemeinen Einsatzes von Robotern auf die Arbeitswelt durchzudenken. Der Chirurg Laurent Alexandre erwartet, dass um 2040 niemand mehr akzeptiert, von menschlicher Hand operiert zu werden, genauso wie wir heute uns weigern würden, ein Flugzeug mit ausgeschaltetem Bordcomputer zu besteigen. Wenn die Robotik selbst zu derart komplexen Bewegungen wie denen eines Chirurgen fähig sein wird, werden wesentlich weniger qualifizierte Arbeitsposten verschwinden. Die enormen durch die Robotik erreichten Produktivitätsgewinne würden es wohl erlauben, den Verlust der Jobs mit einem von jeder Arbeit unabhängigen Mindesteinkommen zu kompensieren.

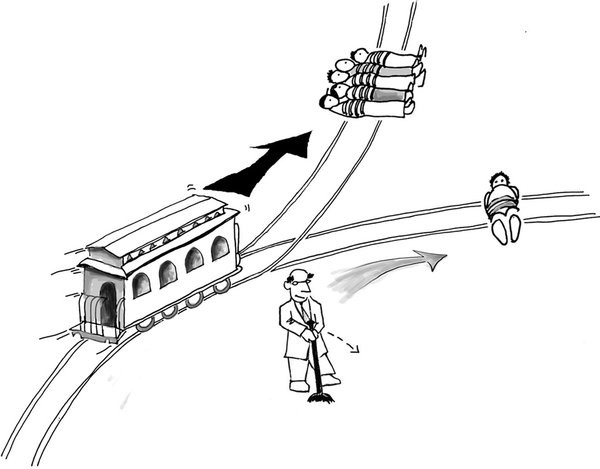

Ehe man beginnt, von einem künftigen Paradies zu träumen, sollte man sich darauf einstellen, dass diese Entwicklungen kaum friedlich ablaufen dürften. Gegen Transhumanisten werden sich „Bio-Konservative“ formieren: die Mehrheit der Umweltschützer, Souveränisten, die auf die Unabhängigkeit ihrer Nationen setzen, die etablierten Religionen und wohl auch die Verlierer der neuen Entwicklung, von denen ein Teil aus Verzweiflung gewaltsam gegen die künstliche Intelligenz vorgehen würde. Die Neo-Ludditen des RIFT (im England des beginnenden 19. Jahrhunderts zerstörten die Ludditen die ersten Spinnereien der Textilindustrie), wie sie in Transcendence zu sehen sind, wären nicht so fern der Realität.

Bereits 2013 warnten Google-CEO Eric Schmidt und der junge Jared Cohen, ein demokratischer Ex-Diplomat, der den Thinktank Google Ideas leitet, in ihrem Buch The New Digital Age davor, dass die 52 Prozent der Weltbevölkerung unter 30, die in benachteiligten Regionen leben, ein enormes gewaltbereites Reservoir bildeten – und dass nur die Firmen, die sich mit Spitzentechnologie beschäftigen, dieses Reservoir zähmen könnten.

Abschließende Worte von George Dyson, einem US-Wissenschaftshistoriker mit bemerkenswerter Laufbahn: Seine Eltern waren Professoren am berühmten Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton (er Physiker, sie Mathematikerin), seine Babysitterin die Assistentin von Einstein. Dyson selbst verließ sein komfortables Lebensumfeld, um zwanzig Jahre lang in einem Baumhaus zu leben und, wie die Ureinwohner von Alaska, Kajaks zu bauen.

Für diesen atypischen Beobachter sollten sich die Menschen nichts vormachen: Die Maschinen haben schon die Oberhand. Und ihr „Urteilsvermögen“ werde vielleicht das der Institutionen, „denen wir so lange die Macht anvertraut haben, wie der Kirche, die sie nicht notwendigerweise gut genutzt haben“, übertreffen. Die Technologie, hat Dyson dem französischen Dokumentaristen Antoine Viviani erklärt, sei „ein umfassenderer Geist als der des Menschen“, ein Geist, der „Fähigkeiten besitzt, die wir in der Religion suchen, um den Tod zu überwinden“. Wir erleben die Geburt eines neuen Universums, „als ob man im Teleskop die ersten Sekunden nach dem Big Bang beobachten würde“. Und wenn einmal künftige Generationen („sollte es sie noch geben“, fügt er mit trockenem Humor hinzu) auf unsere Epoche zurückblicken, werden sie sich sagen: „Welch eine Chance hatten sie, all das mitzuerleben.“ Aber Dyson warnt uns: „Vielleicht wartet der Teufel noch immer, und er will sich der Computer bedienen. Unsere Aufgabe als menschliche Wesen ist es, sicherzustellen, dass die Computer nicht die Instrumente des Teufels werden. Dass sie das sein könnten, wäre durchaus möglich.“ (Joëlle Stolz, 7.6.2015)“

Kin Cheung/APThey aren’t building cars.

Kin Cheung/APThey aren’t building cars.